Reconstruction by Eric Foner ***(of 4)

As part of my ongoing attempt to learn the American history I should have been taught I continue to read histories of Blacks, Indians, women, workers, and immigrants. Among the eras I have heard about, but knew comparatively little is Reconstruction, the period immediately following the end of the Civil War.

The simple description is the North won the war. Foner's encyclopedic description of the decades that followed strongly suggest that though the America was reassembled, it was not reunified, and that the battle over emancipation and the rights of Blacks to vote freely and fully participate in the economy of the nation has still not been won. In many ways, the South lost the Civil War, but won its battle for White Supremacy. Witness the 2021 southern legislatures forbidding the teaching of Black History in schools (derogatorily called Critical Race Theory when in reality it should be called American History) and ongoing attempts to limit access for Black voters. I digress, though not very far.

When General Lee signed the terms of surrender in 1865 the North had to figure out how to reintegrate southern states and southerners who fought to the death to protect their right to enslave Americans of African descent. The north sent occupying forces and for a short period of time passed legislation to raise the status of enslaved Blacks from non-citizens, or three-fifths of a person, to full participants. The 13th Amendment ended slavery. The 14th Amendment awarded Blacks the right to vote (but not females of any race or Indians). The 15th Amendment had to be passed, because even though Southern states were under occupation by northern troops, and the law said Blacks had to be given access to the polls, Southerners found ways of inhibiting Black participation in the the electoral process. (Sound familiar, Georgia?)

For a brief period in American history, the South was forced to act as if Blacks were full citizens. Black men were elected to Congress. They served in state and local governments and for the first time in history on juries. Former slaves went to school for the first time and opened businesses. It was conceivable they a Black man could own land, the basis for wealth-making, or at least subsistence agriculture. The idea of Black equality with whites was so unusual, Republicans of the day (in those days Republicans were progressive) that supported Black equality were called Radicals. Pause for a moment and consider what it means that historians have labeled the politicians who believed Blacks were people like all other people were considered RADICALS.

Within a decade of the war's end, however, Southern politicians, called Redeemers, backed by northern politicians tired of policing the south, succumbed to deeply held racist beliefs. Across the south intimidation, brutal force, murder, and massacre reestablished America's caste system.

|

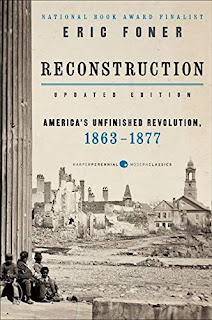

| An etching of black families gathering the dead after the Colfax Massacre published in May 10, 1873. |

The number of massacres in which white mobs slaughtered crowds of Blacks was so numerous (and unbeknownst to me) that the Tulsa annihilation (also news to me within the last couple of years) appears to be simply one small example in an unending war of white vigilantism.

Eric Foner wrote his book in 1988 in what evidently was a groundbreaking reinterpretation of the period. Previously, historians thought Reconstruction failed to empower Blacks because Blacks were lazy, childlike, uneducable, and generally incapable of assuming full responsibility as citizens. Reading Foner is like checking every southern newspaper, every day, for ten years. It is that comprehensive. Amazing that 35 years after its publication, so few of us white people know anything about our own history of how the Civil War is ongoing.

Comments

Post a Comment