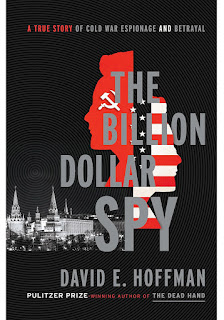

The Billion Dollar Spy by David E. Hoffman *** (of 4)

At the beginning of the Cold War, America had no on-the-ground spy in Moscow. At a time when competition between the United States and the Soviet Union included everything from sports matches to direct military conflicts, albeit in other countries around the world, knowing something about what the opposition was capable of on a field of war was absolutely necessary. The best way to find out was to have someone tell you, smuggle documents, or hand photographs taken in secret to a CIA case manager.

| ||

| A painting of Adolf Tolkachev, by Kathy Krantz Fieramosca, hangs at CIA headquarters. Illustrates SPY (category i), by David E. Hoffman © 2015, The Washington Post. Moved Friday, July 3, 2015.

Adolf Tolkachev hated Stalin and the Soviet authorities with such ardor he courted the CIA until they finally paid him the attention he deserved. Tolkachev was a missile engineer with access to the very documents that could tell the CIA, and thus the U.S. military, precisely what capacity the USSR had with respect to delivering long range missiles toward American targets and the progress it was making with Russian radar used to detect incoming planes and ordinance.

The book is nostalgic for the days when spy vs. spy shenanigans in Moscow involved hiding film cameras inside pens, notes written with invisible ink, dead dropped messages into hollow logs, cardboard passengers in cars to outsmart a tailing spy network, sending signals by timing the lighting of a kitchen lamp, or carefully placed lipstick smears on phone booths. Still, every maneuver between spy and handler had to be analyzed for the possibility of misinformation being coordinated by a double or triple agent.

Behind all the kitschy gadgets, however, lay the prospect of direct nuclear confrontation, a threat that loomed large from the 1950s through the 1980s and in reality, like the spycraft that continues, has never fully disappeared.

|

Comments

Post a Comment